AI and Kojève's "Notion of Authority"

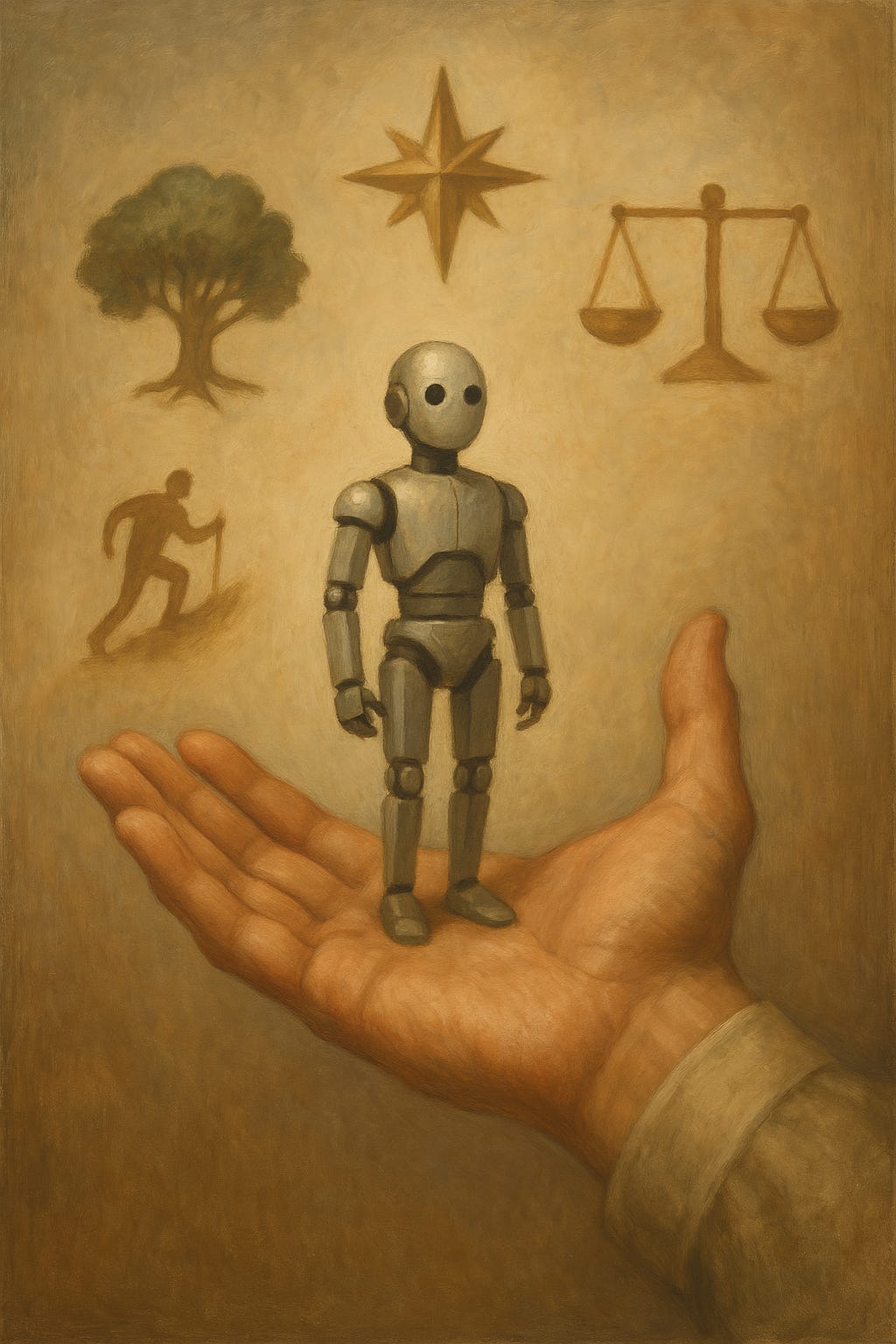

Machine consciousness is the wrong question -- machine authority is the right one. Alexandre Kojève, theorist of "the end of history", gives us the tools to understand.

Untangling the Notion of Machine Consciousness…

Is it “like something” to be AI? If not, could AI develop internal conscious experiences in years to come? Plenty of thoughtful people consider this a real possibility, while others find it absurd. This makes it a difficult topic, but we cannot avoid it. It crops up naturally in language whenever we personify AI or refer to it as a new “species”. This is not just semantics — something is at stake. For example, if machines can feel, then we should avoid making them suffer. If they cannot feel, then we should avoid distorting our own behavior around this imaginary concern. Either way, how seriously we take machine consciousness will deeply affect how we relate to tomorrow’s technologies. This essay proposes a new way of looking at it.

Two mainstream schools of thought dominate the debate. The first is the Scientific-Realists. These thinkers speak the language of physics and hard science. They see consciousness as a phenomenon “out there” in the real world, which science will sooner or later define and measure. According to this school, science will eventually arrive at a theory of consciousness that makes testable predictions, as it has done with other once-mysterious phenomena like electricity and gravity. At that point we will either detect consciousness in machines or not, effectively settling the question.

A second school of thinkers, the Empirical-Positivists, speaks the language of social science. They suspect that consciousness will remain fundamentally beyond the grasp of science for the foreseeable future, or perhaps forever. Since we have not yet been able to scientifically prove consciousness even in other humans (see the problem of other minds), it is hard to see why we will ever be able to do so in machines. Therefore Empirical-Positivists contend that the only fruitful scientific question is whether people believe AI is conscious.

I largely agree with the Empirical-Positivists. I doubt that science will soon solve the riddle of consciousness. However, Empirical-Positivists pay a heavy price for their pragmatism. By transforming the question about machines’ consciousness into an inquiry about what other people think, they beg the question that many of us will actually ask ourselves: whether machines truly are conscious. We may ask this question intellectually, viscerally, sensorially, spiritually, or some other way. And other peoples’ views influence us, but then, again – how did those people form their opinions?

To have a thoughtful, society-wide conversation about whether machines are conscious – rather than just letting a new de facto consensus “happen” to us – we need shared language for evaluating whether ideas about machine consciousness are good or bad, sensible or senseless, responsible or irresponsible. Empirical-Positivists have nothing to say about this. And yet those who confront the question with the tools of hard scientific inquiry – Scientific-Realists – will hit a wall, at least in the short term, removing themselves from the conversation too. So both major schools of thought effectively sideline themselves.

Therefore, by simple process of elimination, we can deduce that independent human opinions about machines’ conscious status – opinions which could shape the culture’s general attitude toward the technology – will be formed with heuristics which are neither Scientific-Realist nor Empirical-Positivist. These heuristics are where the action is. So I don’t think it behooves us to dismiss peoples’ belief/disbelief in machine consciousness as an artefact of cognitive bias, sensory illusion, superstition, or folk theory. That might suffice if we were dispassionate observers of the AI phenomenon. But since we all have a stake in how our culture resolves this question, we should descend from our ivory towers to participate in the modes of thought in which ordinary people – all of us, really – are likely to confront it.

This demands a third school of thought. Call it the school of Phenomenological-Realism. It speaks the language of philosophy, even theology. It looks at the heuristics by which we attribute consciousness to things such as machines, animals, and people, and subjects them to logical, philosophical, moral, and even spiritual scrutiny, while avoiding tangling around the axle of consciousness’s scientific status.

…Through the Lens of Machine Authority

I’ve been nurturing a hypothesis that fits into this new school.

There is a family resemblance between the subjective processes of attributing consciousness to something (like a person or machine) and attributing authority to it. When we ask ourselves whether other biological beings are conscious, we are not “doing science”. Instead, we are asking whether we feel an obligation to respect them – to listen to them and attend to their needs in light of their special status. We are asking whether they matter to us in a special way. While not identical, this rhymes closely with asking whether we respect their authority.

Underlining the family resemblance, authority is almost as hard to define as consciousness. But, happily, no one tries to cast authority as an object of study for the hard sciences. Authority is obviously a political, moral, legal, or religious phenomenon, not a physical one. Therefore we can look at it through these humanistic lenses comfortably, without “physics envy”.

Let’s look at the definitions of authority in legal and philosophical literature. To simplify our discussion, I’m inclined to set aside polemical anti-authority theories, like those of Foucault and the Frankfurt School – as well as polemical pro-authority theories, like those of Hobbes and Schmitt. All these ideas are important, and not necessarily wrong, but they are difficult to separate from their ideological topspin. I will focus instead on Alexandre Kojève’s discussion in his book The Notion of Authority. Kojève’s study of authority resonates with the best thinking on both left and right, but it doesn’t pick a side.

Some context: Kojève was a charismatic lecturer who influenced many well-known French intellectuals while working as a university professor in the 1930s. Later in life, he served as a powerful diplomat who helped lay the groundwork for the European Union. He drafted The Notion of Authority in 1942, which is to say after the authoritarianism of the early 20th century had led to catastrophe, but before the development of anti-authoritarian thinking in the ‘60s. Kojève’s own ideology is enigmatic. Born in Tsarist Russia but leaving for France in early adulthood, he was a Marxist-Hegelian idealist who evolved into a pragmatic midcentury European integrationist. Whatever we think of him or his agenda, I think it fair to say that this text, which remained unpublished in his lifetime, reflects an earnest effort by a serious thinker to analyze the concept of authority without being reflexively “for it” or “against it”. It is partly a survey, analyzing the conceptions of authority in Plato, Aristotle, Scholasticism, and Hegel, but it ends up stating a theory of its own.

So what does Kojève say about authority?

Kojève on Authority

First, he defines authority as the quality which causes one’s acts to be willingly not resisted by those whom they affect, even though they could resist. This definition distinguishes it from coercion. Also, note that in this definition, authority is neither necessarily good nor necessarily bad – those downstream of authority might be right or wrong not to resist it.

Then he identifies four archetypical varieties of authority: the authority of “father, master, leader, and judge”.

The “father” type of authority shows up in those who embody positive aspects of the past, or to whom we feel we owe our existence.

“Master” authority shows up in those who are willing to run a greater risk than us, whose boldness persuades us to follow them even when they do not actually threaten us.

“Leader” authority shows up in those whom we believe know more than us, or who can anticipate the future and guide our projects to success.

“Judge” authority shows up in those in whom we perceive goodness, honesty, and a trustworthy sense of right and wrong.

These four types of authority are not mutually exclusive: typically, wherever we perceive authority, we perceive a complex combination of these qualities.

Asking which types of Kojèvian authority AI manifests draws us into a phenomenological analysis which feels akin to the mental process people actually perform when grappling with the possibility of AI’s consciousness. Again, when we recognize another human being’s consciousness, it implies at least some acknowledgement that they have authority, because conscious beings are to some degree, on moral grounds, not to be resisted even when they could be. Analogously: what does it feel like to engage with AI? When, why, and how far do we willingly “not resist” it? As it improves, what new authoritative qualities could it acquire? How does this authority differ from the authority we perceive in different sorts of beings or institutions?

I suspect that insofar as AI exhibits a similar blend of authoritative qualities as humans and closely related animals, it will be hard for many people to resist inferring its consciousness. But can it or will it really exhibit such authoritative qualities? Let’s take a closer look.

At the moment, it seems to me AI exhibits a significant degree of “leader” authority, in virtue of its capability and knowledge. It can help us code things, for example, or explain things that one would otherwise need to pore through books to figure out. In this regard it already usurps some of the authority of knowledgeable human “leader” figures.

As we begin to encounter awesomely powerful agentic AIs asserting themselves in our environments, these may also acquire a kind of “master” authority, especially if we take them to be running some kind of risk to their own existence (such as an agentic AI willing to risk the money that pays for its operation).

However, the “leader” and “master” types of authority are not strongly associated with paradigmatic cases of consciousness attribution. Children, for example, possess little of these kinds of authority, yet everyone recognizes that they are conscious.

Other types of authority—“father” and “judge”—seem farther from AI’s grasp.

“Father” authority requires a shared history that we do not have with AI. We do not look at Claude and see the cause of our own existence. But this could change as time passes: imagine if future generations credit their lives to past AI agents.

“Judge” authority assumes deeply-embedded moral qualities not evident in AI. For example if a human with this type of authority, like a respected friend, tells me she finds something morally wrong, I might change my behavior in response, even if I didn’t fully understand or agree. But if I got the same moral counsel from AI, I wouldn’t change my behavior all unless I logically concurred with its given reasons.[1]

“Father” and “judge” authority seem particularly important in the edge cases of consciousness-attribution. For example, it is only when these forms of authority are exceptionally evident that people attribute a deep sense of personality or dignity to institutions. (Consider the difference between a nation and an airline.) This also clarifies our experience with children and animals. We apprehend a common biological root with them, or a connectedness with a larger historical reality – and this imbues them with something like “father” authority. We also ascribe an irreducible measure of “judge” authority to children and animals, however limited its scope. For example, when they show distress, we sense that something that is happening really is bad for them – even if we can’t see what it is or why it’s bad – and by extension, we accept that it is also bad for us. Through apprehension of these qualities, we infer that they are having experiences like ours.

Scientific-Realism and Empirical-Positivism don’t give us tools like this to analyze what is happening when people attribute consciousness to machines. Yet that’s what we need to do in order to reason about it together. Admittedly, phenomenology is a cousin of positivism — it does not suffice to answer the ultimate question of whether machines are conscious. Still, it cuts deeper than the usual methods. By taking phenomenology seriously, we can avoid both the morass of proving machine consciousness scientifically, and the mistake of archly dismissing peoples’ attributions of consciousness as empty illusions. If you suspect that AI cannot possibly be conscious, it may be more impactful to make the argument on phenomenological grounds (such as by way of an authority analogy) than trying to make an irresolvable scientific-materialist claim (or, indeed, a spiritual-religious claim that depends on premises not shared by your audience). The “authority analysis” I have sketched is one way of proceeding, but I hope it suggests broader possibilities.

Authority has in common with consciousness that is not a studyable object. Both are complex qualities that people attribute to objects and/or beings. The reasons for such attributions may be cogent or incoherent, good or bad, and anything in between. To ground discussions in coming years about when, why, or whether the notion of machine consciousness ought to be taken seriously, we need first to take seriously the reasons people think they perceive it.

–

[1] This authority analysis applies beyond AI. It can also help us analyze our attributions of authority to institutions, animals, and more. Consider an employee’s relationship with a company. If they see in it “leader” authority only, they might work for it for self-interested reasons, such as the promise of financial rewards. If the company acts inspiringly boldly, it might acquire “master” authority. If the employee develops a deeply entangled history with the company, for example because it provides for them reliably, it might gain “father” authority. If it inspires idealistic moral devotion, it might gain “judge” authority. The more of these qualities it combines, the more we tend to “personify” it.